"Do you only ever wear black?"

Now there's a question I hadn't been asked since I was about 17. Don't know. Hadn't really thought about it. The months of summer bring a world of archaeological fieldwork and the assorted muted greys, greens and khaki colours of combat-dig-wear, but full on winter-lecture mode....?

"Er"

Strange question for a student to ask.

When I first started in academia, some 25 years ago now, the university-powers-that-be did attempt (briefly) to enforce a dress code on their staff - something about lecturers having to regularly look smarter (at least in clothing choice) than their students (so that the two tribes could, perhaps, be more easily distinguished). Some hope. I did once toy (very briefly) with the concept of jackets / shirts / ties / waistcoats. Silly idea. Not me at all.

In the world of pop culture archaeological academia, of course, as I've noted before, we've got the great Dr Jones as a role model, slipping effortlessly from the monotonous world of chalk and talk, where tweed and sensible ties rule supreme

to the battered leather jacket and fedora prefered when looting (sorry, conducting serious archaeological fieldwork)

There are no hard and fast dress codes when it comes to real world archaeo-academia though (as a glimpse at any university archaeology undergraduate programme will no doubt amply demonstrate). There was a time when (I think) I did wear colours (albeit mostly baby sick and food stains) but dark clothing does help one to blend into the gloom of a poorly lit lecture theatre just as khaki, I guess, helps the avid archaeo-practitioner blend into the dusty fields surrounding the average dig (perhaps archaeologists simply don't want to be seen?).

Many years ago, when I first dipped my toe in the world of televisual archaeology, a producer in the know told me that, if I wanted to work full time in TV (which, at the time, I wasn't really convinced that I did) I needed to be noticed. "Get a distinctive personality trait" he advised, "something that gets you remembered. Better still" he went on "dye your hair, get a tattoo or some form of prominent facial piercing. Even better than that" he grinned "wear brightly coloured or hideously mismatched clothing. In short, you need to stand out from the crowd".

Having not gone to art school (and having already completed my undergraduate experiments in clothing - all best forgotten) I remained stubbornly unmemorable and dressed as myself, contrary to the advice given.

Over the last couple of months, as I gorge on my daily lunchtime diet of Bargain Hunt (don't worry, I do still have a job), I can't help but notice that this advice is, apparently, still being given (and actually being heeded by those in the auction-related world). All it takes for experts to be remembered (and re-employed) is to create a TV persona based on distinctively memorable clothing. Hence there's the distinctive, brightly coloured scarf:

the distinctive, brightly coloured hat:

the distinctive scarf and hat:

Now there's a question I hadn't been asked since I was about 17. Don't know. Hadn't really thought about it. The months of summer bring a world of archaeological fieldwork and the assorted muted greys, greens and khaki colours of combat-dig-wear, but full on winter-lecture mode....?

"Er"

Strange question for a student to ask.

When I first started in academia, some 25 years ago now, the university-powers-that-be did attempt (briefly) to enforce a dress code on their staff - something about lecturers having to regularly look smarter (at least in clothing choice) than their students (so that the two tribes could, perhaps, be more easily distinguished). Some hope. I did once toy (very briefly) with the concept of jackets / shirts / ties / waistcoats. Silly idea. Not me at all.

In the world of pop culture archaeological academia, of course, as I've noted before, we've got the great Dr Jones as a role model, slipping effortlessly from the monotonous world of chalk and talk, where tweed and sensible ties rule supreme

to the battered leather jacket and fedora prefered when looting (sorry, conducting serious archaeological fieldwork)

There are no hard and fast dress codes when it comes to real world archaeo-academia though (as a glimpse at any university archaeology undergraduate programme will no doubt amply demonstrate). There was a time when (I think) I did wear colours (albeit mostly baby sick and food stains) but dark clothing does help one to blend into the gloom of a poorly lit lecture theatre just as khaki, I guess, helps the avid archaeo-practitioner blend into the dusty fields surrounding the average dig (perhaps archaeologists simply don't want to be seen?).

Many years ago, when I first dipped my toe in the world of televisual archaeology, a producer in the know told me that, if I wanted to work full time in TV (which, at the time, I wasn't really convinced that I did) I needed to be noticed. "Get a distinctive personality trait" he advised, "something that gets you remembered. Better still" he went on "dye your hair, get a tattoo or some form of prominent facial piercing. Even better than that" he grinned "wear brightly coloured or hideously mismatched clothing. In short, you need to stand out from the crowd".

Having not gone to art school (and having already completed my undergraduate experiments in clothing - all best forgotten) I remained stubbornly unmemorable and dressed as myself, contrary to the advice given.

Over the last couple of months, as I gorge on my daily lunchtime diet of Bargain Hunt (don't worry, I do still have a job), I can't help but notice that this advice is, apparently, still being given (and actually being heeded by those in the auction-related world). All it takes for experts to be remembered (and re-employed) is to create a TV persona based on distinctively memorable clothing. Hence there's the distinctive, brightly coloured scarf:

the distinctive, brightly coloured hat:

the distinctive scarf and hat:

the distinctive trousers:

the distinctive blazer:

and, most memorable of all, the distinctive hat, scarf, bow tie, coat and facial hair combo:

In comparison with this, how can the average real world archaeologist compete?

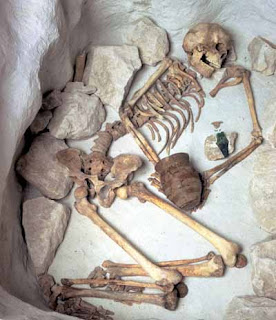

Dark (unmemorable) colours for clothing then it must remain for me...at least until I fade and become part of the archaeology myself.